Authentic or forgery? I strike today’s imagination.

I evoke the resourcefulness of adventurers who once braved the unknown.

Who am I??

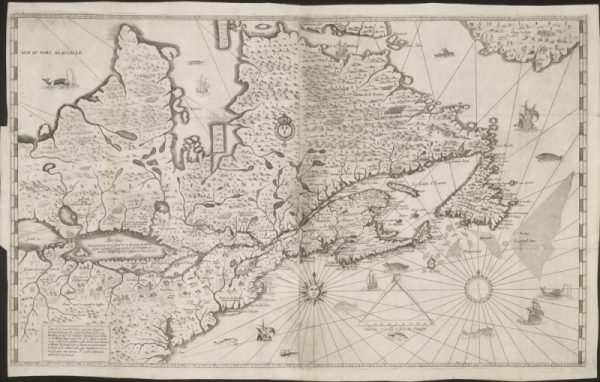

The maps produced by Samuel de Champlain are fascinating: they are so accurate that the explorer-geographer has the enviable reputation of having created the first Canadian territory maps considered scientific. In the GPS age, it is hard to imagine that he drew them from rudimentary tools and native allies’ testimonies translated by an interpreter.

In fact, the illustrious man had a secret: his astrolabe, a brass disc that was of untold use to him in the early 17th century, but which has also been at the center of a whole saga since 1867.

“Let us prepare the road for those who will follow”, wrote Champlain. The man who would become known as the father of New France could not have said it better or done it better.

A captivating journey

The summer of 1867. Near Cobden, a young 14 year old man clears a land. While doing so, Edward George Lee discovers an astrolabe made in France in 1603.

The summer of 1867. Near Cobden, a young 14 year old man clears a land. While doing so, Edward George Lee discovers an astrolabe made in France in 1603.

What was the instrument doing on this land, between two lakes, known today as the Astrolabe and Muskrat? On June 7, 1613, in the middle of a portage, did Samuel de Champlain lose or abandon the astrolabe he was using to draw his maps?

This is what believed by the famous explorer’s travel accounts’ readers, first published in 1870. After all, Champlain had noted, in his journal, that the portages had forced him to lighten his baggage. Moreover, from that point on, his explorations maps from Huronia (today’s southern Georgian Bay) to the mouth of Lake Ontario are distorted. Is it because he no longer recorded the latitude, as the astrolabe allowed?

In 1990, researchers set the record straight: Champlain probably never touched the astrolabe unearthed by Edward George Lee. Why would the explorer, who wrote everything down in his logbook, not mentioned that he had left behind his precious tool? And would really a cartographer handle a 13 cm pocket size tool? Was it an auxiliary instrument? Skepticism redoubled when faced with the unexplained presence of possibly liturgical cups near the astrolabe, upon its discovery in 1867.

In 1990, researchers set the record straight: Champlain probably never touched the astrolabe unearthed by Edward George Lee. Why would the explorer, who wrote everything down in his logbook, not mentioned that he had left behind his precious tool? And would really a cartographer handle a 13 cm pocket size tool? Was it an auxiliary instrument? Skepticism redoubled when faced with the unexplained presence of possibly liturgical cups near the astrolabe, upon its discovery in 1867.

One thing is certain: this astrolabe, found in the Ottawa Valley over 150 years ago, has seen a lot of country! The brass circle crossed the Atlantic and was used to orient oneself in the New World, was lost and then buried in the Cobden lands… After emerging, it was passed for 75 years from hand to hand before being acquired by the New York Historical Society in 1942. Today, the treasure is safely stored in a vault at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau.

The building of a myth

At the time of Edward George Lee’s discovery, modern Canada was being cemented. It is said that Champlain’s astrolabe served as a pretext to fuel the myth of a great nation[1].

This was followed in 1915 by the erection of Champlain’s statue at the top Ottawa’s grandiose Nepean Point[2], overlooking the Ottawa River. It was – and still is – as if Champlain was watching over the great river he had sailed 300 years earlier – while also watching over the Museum of History, which today stands just across the Alexandra Bridge.

In 1948, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada recognized that the astrolabe discovery, astrolabe that was possibly abandoned by Champlain in 1613, as a national historic event and established a monument south of Cobden on the east side of Highway 17, adjacent to Astrolabe Lake (and today’s LOGOS Land tourist attraction).

During the 1967 Canadian Confederation’s Centennial celebrations, the astrolabe was elevated as a Canadian history symbol. Astrolabe’s copies were cast and displayed in museums across the country, such as in Pembroke, and in the United States. Some 20 years later, as the Canadian government prepared to open a major history museum, it invested $250,000 to repatriate the original instrument.

By the 1990s, the instrument’s true origin was in doubt, so much so that authorities questioned the stone monument appropriateness’ in Cobden. Out of respect for the area’s population, the base and plaque remained in place, but nothing of that epic appears on the list of federal heritage designations.

Courtoisie du Musée de la piste Champlain – Champlain Trail MuseumIt is, however, worth a visit – after all, the Cobden lands have held the astrolabe for over 250 years. So is the Champlain Trail Museum in Pembroke, where the object’s replica is kept. Champlain actually walked those lands, symbolizing the march of our ancestors into the unknown, highlighting their grit and strength of character. This astrolabe has become a myth, a symbol of Samuel de Champlain’s resourcefulness and of so many others…

The artifact has only returned once to the Ottawa Valley after the great 1867 discovery. That was in 2013, the 400th anniversary of Samuel de Champlain’s first passage this high up the Ottawa River. Two years later, the 400th anniversary of Champlain’s passage across Georgian Bay was celebrated. For the occasion, a huge astrolabe was erected on the spot where Champlain made landfall, now the town of Penetanguishene.

Parc Rotary, PenetanguisheneThe astrolabe’s symbol is well established, despite the controversy that surrounds it. This is the traits of a legend.

Champlain’s astrolabe: a mythical object, and of course a pretext to cement the nation in 1867, a pretext to promote Canadian unity in 1967, and today, a pretext to go on an adventure. And to retrace the explorer’s route on the Champlain Tourist Route in Ontario.

[1] Some people even question the year it was built, 1867. It would be 12 years before the story of Cobden was put down on paper, after having circulated by word of mouth.

[2] Of note: Nepean Point is undergoing its first phase of redevelopment in 2019-2020.

Pour refaire le parcours de l’explorateur sur la Route touristique Champlain de l’Ontario.

To retrace the astrolabe’s route, follow this 150 km path:

- The Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau

- The Champlain statue overlooking Nepean Point and the Ottawa River

- Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaque, south of Pembroke

- The Champlain Trail Museum in Pembroke

Written by Andréanne Joly

You must be logged in to post a comment.